This is a walkthrough of the HTB Academy Module for Stack-Based Buffer Overflow on Linux x86.

Buffer Overflow Introduction:

Buffer overflows are among the most common security vulnerabilities in software applications that can be exploited over the Internet. In short, buffer overflows are caused by incorrect program code, which cannot process too large amounts of data correctly by the CPU and can, therefore, manipulate the CPU’s processing.

A buffer overflow can cause the program to crash, corrupt data, or harm data structures in the program’s runtime. The last of these can overwrite the specific program’s return address with arbitrary data, allowing an attacker to execute commands with the privileges of the process vulnerable to the buffer overflow by passing arbitrary machine code. This code is usually intended to give us more convenient access to the system to use it for our own purposes. Such buffer overflows in common servers, and Internet worms also exploit client software.

A particularly popular target on Unix systems is root access, which gives us all permissions to access the system. However, as is often misunderstood, this does not mean that a buffer overflow that “only” leads to the privileges of a standard user is harmless. Getting the coveted root access is often much easier if you already have user privileges.

Buffer overflows, in addition to programming carelessness, are mainly made possible by computer systems based on the Von-Neumann architecture.

The most significant cause of buffer overflows is the use of programming languages that do not automatically monitor limits of memory buffer or stack to prevent (stack-based) buffer overflow. These include the C and C++ languages, which emphasize performance and do not require monitoring.

For this reason, developers are forced to define such areas in the programming code themselves, which increases vulnerability many times over. These areas are often left undefined for testing purposes or due to carelessness. Even if they were used for testing purposes, they might have been overlooked at the end of the development process.

Exploit Development Introduction

Exploit development comes in the Exploitation Phase after specific software and even its versions have been identified. The Exploitation Phase goal is to use the information found and its analysis to exploit the potential ways to gain interaction and/or access to the target system.

Developing our own exploits can be very complex and requires a deep understanding of CPU operations and the software’s functions that serve as our target. Many exploits are written in different programming languages. One of the most popular programming languages for this is Python because it is easy to understand and easy to write with. In this module, we will focus on basic techniques for exploit development, as a fundamental understanding must be developed before we can deal with the various security mechanisms of memory.

Before we run any exploits, we need to understand what an exploit is. An exploit is a code that causes the service to perform an operation we want by abusing the found vulnerability. Such codes often serve as proof-of-concept (POC) in our reports.

There are two types of exploits. One is unknown (0-day exploits), and the other is known (N-day exploits).

0-Day Exploits

An 0-day exploit is a code that exploits a newly identified vulnerability in a specific application. The vulnerability does not need to be public in the application. The danger with such exploits is that if the developers of this application are not informed about the vulnerability, they will likely persist with new updates.

N-Day Exploits

If the vulnerability is published and informs the developers, they will still need time to write a fix to prevent them as soon as possible. When they are published, they talk about N-day exploits, counting the days between the publication of the exploit and an attack on the unpatched systems.

Also, these exploits can be divided into four different categories:

1

2

3

4

Local

Remote

DoS

WebApp

Local Exploits

Local exploits / Privilege Escalation exploits can be executed when opening a file. However, the prerequisite for this is that the local software contains a security vulnerability. Often a local exploit (e.g., in a PDF document or as a macro in a Word or Excel file) first tries to exploit security holes in the program with which the file was imported to achieve a higher privilege level and thus load and execute malicious code / shellcode in the operating system. The actual action that the exploit performs is called payload.

Remote Exploits

The remote exploits very often exploit the buffer overflow vulnerability to get the payload running on the system. This type of exploits differs from local exploits because they can be executed over the network to perform the desired operation.

DoS Exploits

DoS (Denial of Service) exploits are codes that prevent other systems from functioning, i.e., cause a crash of individual software or the entire system.

WebApp Exploits

A Web application exploit uses a vulnerability in such software. Such vulnerabilities can, for example, allow a command injection on the application itself or the underlying database.

CPU Architecture

The architecture of the Von-Neumann was developed by the Hungarian mathematician John von Neumann, and it consists of four functional units:

1

2

3

4

Memory

Control Unit

Arithmetical Logical Unit

Input/Output Unit

In the Von-Neumann architecture, the most important units, the Arithmetical Logical Unit (ALU) and Control Unit (CU), are combined in the actual Central Processing Unit (CPU). The CPU is responsible for executing the instructions and for flow control. The instructions are executed one after the other, step by step. The commands and data are fetched from memory by the CU. The connection between processor, memory, and input/output unit is called a bus system, which is not mentioned in the original Von-Neumann architecture but plays an essential role in practice. In the Von-Neumann architecture, all instructions and data are transferred via the bus system.

Von-Neumann Architecture

Memory

The memory can be divided into two different categories:

1

2

Primary Memory

Secondary Memory

Primary Memory

The primary memory is the Cache and Random Access Memory (RAM). If we think about it logically, memory is nothing more than a place to store information. We can think of it as leaving something at one of our friends to pick it up again later. But for this, it is necessary to know the friend’s address to pick up what we have left behind. It is the same as RAM. RAM describes a memory type whose memory allocations can be accessed directly and randomly by their memory addresses.

The cache is integrated into the processor and serves as a buffer, which in the best case, ensures that the processor is always fed with data and program code. Before the program code and data enter the processor for processing, the RAM serves as data storage. The size of the RAM determines the amount of data that can be stored for the processor. However, when the primary memory loses power, all stored contents are lost.

Secondary Memory

The secondary memory is the external data storage, such as HDD/SSD, Flash Drives and CD/DVD-ROMs of a computer, which is not directly accessed by the CPU, but via the I/O interfaces. In other words, it is a mass storage device. It is used to permanently store data that does not need to be processed at the moment. Compared to primary memory, it has a higher storage capacity, can store data permanently even without a power supply, and works much slower.

Control Unit

The Control Unit (CU) is responsible for the correct interworking of the processor’s individual parts. An internal bus connection is used for the tasks of the CU. The tasks of the CU can be summarised as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Reading data from the RAM

Saving data in RAM

Provide, decode and execute an instruction

Processing the inputs from peripheral devices

Processing of outputs to peripheral devices

Interrupt control

Monitoring of the entire system

The CU contains the Instruction Register (IR), which contains all instructions that the processor decodes and executes accordingly. The instruction decoder translates the instructions and passes them to the execution unit, which then executes the instruction. The execution unit transfers the data to the ALU for calculation and receives the result back from there. The data used during execution is temporarily stored in registers.

Central Processing Unit

The Central Processing Unit (CPU) is the functional unit in a computer that provides the actual processing power. It is responsible for processing information and controlling the processing operations. To do this, the CPU fetches commands from memory one after the other and initiates data processing.

The processor is also often referred to as a Microprocessor when placed in a single electronic circuit, as in our PCs.

Each CPU has an architecture on which it was built. The best-known CPU architectures are:

1

2

3

x86/i386 - (AMD & Intel)

x86-64/amd64 - (Microsoft & Sun)

ARM - (Acorn)

Each of these CPU architectures is built in a specific way, called Instruction Set Architecture (ISA), which the CPU uses to execute its processes. ISA, therefore, describes the behavior of a CPU concerning the instruction set used. The instruction sets are defined so that they are independent of a specific implementation. Above all, ISA gives us the possibility to understand the unified behavior of machine code in assembly language concerning registers, data types, etc.

There are four different types of ISA:

1

2

3

4

CISC - Complex Instruction Set Computing

RISC - Reduced Instruction Set Computing

VLIW - Very Long Instruction Word

EPIC - Explicitly Parallel Instruction Computing

RISC

RISC stands for Reduced Instruction Set Computer, a design of microprocessors architecture that aimed to simplify the complexity of the instruction set for assembly programming to one clock cycle. This leads to higher clock frequencies of the CPU but enables a faster execution because smaller instruction sets are used. By an instruction set, we mean the set of machine instructions that a given processor can execute. We can find RISC in most smartphones today, for example. Nevertheless, pretty much all CPUs have a portion of RISC in them. RISC architectures have a fixed length of instructions defined as 32-bit and 64-bit.

CISC

In contrast to RISC, the Complex Instruction Set Computer (CISC) is a processor architecture with an extensive and complex instruction set. Due to the historical development of computers and their memory, recurring sequences of instructions were combined into complicated instructions in second-generation computers. The addressing in CISC architectures does not require 32-bit or 64-bit in contrast to RISC but can be done with an 8-bit mode.

Instruction Cycle

The instruction set describes the totality of the machine instructions of a processor. The scope of the instruction set varies considerably depending on the processor type. Each CPU may have different instruction cycles and instruction sets, but they are all similar in structure, which we can summarize as follows:

| Instruction | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. FETCH | The next machine instruction address is read from the Instruction Address Register (IAR). It is then loaded from the Cache or RAM into the Instruction Register (IR). |

| 2. DECODE | The instruction decoder converts the instructions and starts the necessary circuits to execute the instruction. |

| 3. FETCH OPERANDS | If further data have to be loaded for execution, these are loaded from the cache or RAM into the working registers. |

| 4. EXECUTE | The instruction is executed. This can be, for example, operations in the ALU, a jump in the program, the writing back of results into the working registers, or the control of peripheral devices. Depending on the result of some instructions, the status register is set, which can be evaluated by subsequent instructions. |

| 5. UPDATE INSTRUCTION POINTER | If no jump instruction has been executed in the EXECUTE phase, the IAR is now increased by the length of the instruction so that it points to the next machine instruction. |

Stack-Based Buffer Overflow

Buffer overflows are the operating system’s reaction to an error in existing software or during the execution of these. This is responsible for most of the security vulnerabilities in program flows in the last decade. Programming errors often occur, leading to buffer overflows due to inattention when programming with low abstract languages such as C or C++.

These languages are compiled almost directly to machine code and, in contrast to highly abstracted languages such as Java or Python, run through little to no control structure operating system. Buffer overflows are errors that allow data that is too large to fit into a buffer of the operating system’s memory that is not large enough, thereby overflowing this buffer. As a result of this mishandling, the memory of other functions of the executed program is overwritten, potentially creating a security vulnerability.

Such a program (binary file), is a general executable file stored on a data storage medium. There are several different file formats for such executable binary files. For example, the Portable Executable Format (PE) is used on Microsoft platforms.

Another format for executable files is the Executable and Linking Format (ELF), supported by almost all modern UNIX variants. If the linker loads such an executable binary file and the program will be executed, the corresponding program code will be loaded into the main memory and then executed by the CPU.

Programs store data and instructions in memory during initialization and execution. These are data that are displayed in the executed software or entered by the user. Especially for expected user input, a buffer must be created beforehand by saving the input.

The instructions are used to model the program flow. Among other things, return addresses are stored in the memory, which refers to other memory addresses and thus define the program’s control flow. If such a return address is deliberately overwritten by using a buffer overflow, an attacker can manipulate the program flow by having the return address refer to another function or subroutine. Also, it would be possible to jump back to a code previously introduced by the user input.

To understand how it works on the technical level, we need to become familiar with how:

1

2

3

4

the memory is divided and used

the debugger displays and names the individual instructions

the debugger can be used to detect such vulnerabilities

we can manipulate the memory

Another critical point is that the exploits usually only work for a specific version of the software and operating system. Therefore, we have to rebuild and reconfigure the target system to bring it to the same state. After that, the program we are investigating is installed and analyzed. Most of the time, we will only have one attempt to exploit the program if we miss the opportunity to restart it with elevated privileges.

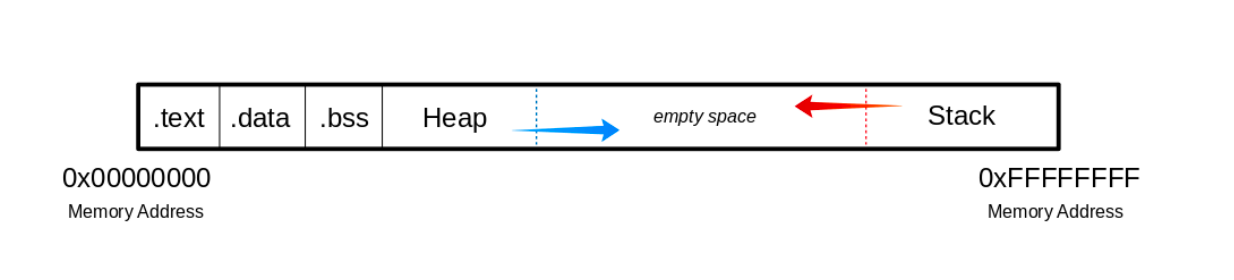

The Memory

When the program is called, the sections are mapped to the segments in the process, and the segments are loaded into memory as described by the ELF file.

Buffer

.text

The .text section contains the actual assembler instructions of the program. This area can be read-only to prevent the process from accidentally modifying its instructions. Any attempt to write to this area will inevitably result in a segmentation fault. .data

The .data section contains global and static variables that are explicitly initialized by the program. .bss

Several compilers and linkers use the .bss section as part of the data segment, which contains statically allocated variables represented exclusively by 0 bits. The Heap

Heap memory is allocated from this area. This area starts at the end of the “.bss” segment and grows to the higher memory addresses. The Stack

Stack memory is a Last-In-First-Out data structure in which the return addresses, parameters, and, depending on the compiler options, frame pointers are stored. C/C++ local variables are stored here, and you can even copy code to the stack. The Stack is a defined area in RAM. The linker reserves this area and usually places the stack in RAM’s lower area above the global and static variables. The contents are accessed via the stack pointer, set to the upper end of the stack during initialization. During execution, the allocated part of the stack grows down to the lower memory addresses.

Modern memory protections (DEP/ASLR) would prevent the execution of such code against buffer overflows. Vulnerable Program

We are now writing a simple C-program called bow.c with a vulnerable function called strcpy().

Bow.c

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

int bowfunc(char *string) {

char buffer[1024];

strcpy(buffer, string);

return 1;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

bowfunc(argv[1]);

printf("Done.\n");

return 1;

}

Disable ASLR

Next, we compile the C code into a 32bit ELF binary. Compilation

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

┌──(root💀kali)-[~/Downloads/hackthebox/bof-module]

└─# gcc bow.c -o bow32 -fno-stack-protector -z execstack -m32

┌──(root💀kali)-[~/Downloads/hackthebox/bof-module]

└─# file bow32 | tr "," "\n"

bow32: ELF 32-bit LSB pie executable

Intel 80386

version 1 (SYSV)

dynamically linked

interpreter /lib/ld-linux.so.2

BuildID[sha1]=9e11d6435455788ef01253074df027de57980c87

for GNU/Linux 3.2.0

not stripped

Vulnerable C Functions

There are several vulnerable functions in the C programming language that do not independently protect the memory. Here are some of the functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

strcpy

gets

sprintf

scanf

strcat

...

GDB Introductions

GDB, or the GNU Debugger, is the standard debugger of Linux systems developed by the GNU Project. It has been ported to many systems and supports the programming languages C, C++, Objective-C, FORTRAN, Java, and many more.

GDB provides us with the usual traceability features like breakpoints or stack trace output and allows us to intervene in the execution of programs. It also allows us, for example, to manipulate the variables of the application or to call functions independently of the normal execution of the program.

We use GNU Debugger (GDB) to view the created binary on the assembler level. Once we have executed the binary with GDB, we can disassemble the program’s main function. GDB - AT&T Syntax

┌──(root💀kali)-[~/Downloads/hackthebox/bof-module]

└─# gdb -q bow32

Reading symbols from bow32...

(No debugging symbols found in bow32)

gdb-peda$ disassemble main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x000011de <+0>: lea ecx,[esp+0x4]

0x000011e2 <+4>: and esp,0xfffffff0

0x000011e5 <+7>: push DWORD PTR [ecx-0x4]

0x000011e8 <+10>: push ebp

0x000011e9 <+11>: mov ebp,esp

0x000011eb <+13>: push ebx

0x000011ec <+14>: push ecx

0x000011ed <+15>: call 0x10b0 <__x86.get_pc_thunk.bx>

0x000011f2 <+20>: add ebx,0x2e0e

0x000011f8 <+26>: mov eax,ecx

0x000011fa <+28>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax+0x4]

0x000011fd <+31>: add eax,0x4

0x00001200 <+34>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax]

0x00001202 <+36>: sub esp,0xc

0x00001205 <+39>: push eax

0x00001206 <+40>: call 0x11a9 <bowfunc>

0x0000120b <+45>: add esp,0x10

0x0000120e <+48>: sub esp,0xc

0x00001211 <+51>: lea eax,[ebx-0x1ff8]

0x00001217 <+57>: push eax

0x00001218 <+58>: call 0x1040 <puts@plt>

0x0000121d <+63>: add esp,0x10

0x00001220 <+66>: mov eax,0x1

0x00001225 <+71>: lea esp,[ebp-0x8]

0x00001228 <+74>: pop ecx

0x00001229 <+75>: pop ebx

0x0000122a <+76>: pop ebp

0x0000122b <+77>: lea esp,[ecx-0x4]

0x0000122e <+80>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gdb-peda$

In the first column, the hexadecimal numbers represent the memory addresses. The numbers with the plus sign (+) show the address jumps in memory in bytes, used for the respective instruction. Next, we can see the assembler instructions (mnemonics) with registers and their operation suffixes. The current syntax is AT&T, which we can recognize by the % and $ characters. | Memory Address | Address Jumps | Assembler Instruction | Operation Suffixes | |—————-|—————|———————–|——————–| | 0x000011de | <+0>: | lea | 0x4(%esp),%ecx | | 0x000011e2 | <+4>: | and | $0xfffffff0,%esp |

The Intel syntax makes the disassembled representation easier to read, and we can change the syntax by entering the following commands in GDB: GDB - Change the Syntax to Intel

gdb-peda$ set disassembly-flavor intel

gdb-peda$ disassemble main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x000011de <+0>: lea ecx,[esp+0x4]

0x000011e2 <+4>: and esp,0xfffffff0

0x000011e5 <+7>: push DWORD PTR [ecx-0x4]

0x000011e8 <+10>: push ebp

0x000011e9 <+11>: mov ebp,esp

0x000011eb <+13>: push ebx

0x000011ec <+14>: push ecx

0x000011ed <+15>: call 0x10b0 <__x86.get_pc_thunk.bx>

0x000011f2 <+20>: add ebx,0x2e0e

0x000011f8 <+26>: mov eax,ecx

0x000011fa <+28>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax+0x4]

0x000011fd <+31>: add eax,0x4

0x00001200 <+34>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax]

0x00001202 <+36>: sub esp,0xc

0x00001205 <+39>: push eax

0x00001206 <+40>: call 0x11a9 <bowfunc>

0x0000120b <+45>: add esp,0x10

0x0000120e <+48>: sub esp,0xc

0x00001211 <+51>: lea eax,[ebx-0x1ff8]

0x00001217 <+57>: push eax

0x00001218 <+58>: call 0x1040 <puts@plt>

0x0000121d <+63>: add esp,0x10

0x00001220 <+66>: mov eax,0x1

0x00001225 <+71>: lea esp,[ebp-0x8]

0x00001228 <+74>: pop ecx

0x00001229 <+75>: pop ebx

0x0000122a <+76>: pop ebp

0x0000122b <+77>: lea esp,[ecx-0x4]

0x0000122e <+80>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gdb-peda$

We don’t have to change the display mode manually continually. We can also set this as the default syntax with the following command. Change GDB Syntax

1

2

┌──(root💀kali)-[~/Downloads/hackthebox/bof-module]

└─# echo 'set disassembly-flavor intel' > ~/.gdbinit

If we now rerun GDB and disassemble the main function, we see the Intel syntax.

GDB - Intel Syntax

──(root💀kali)-[~/Downloads/hackthebox/bof-module]

└─# gdb ./bow32 -q 130 ⨯

Reading symbols from ./bow32...

(No debugging symbols found in ./bow32)

gdb-peda$ disassemble main

Dump of assembler code for function main:

0x000011de <+0>: lea ecx,[esp+0x4]

0x000011e2 <+4>: and esp,0xfffffff0

0x000011e5 <+7>: push DWORD PTR [ecx-0x4]

0x000011e8 <+10>: push ebp

0x000011e9 <+11>: mov ebp,esp

0x000011eb <+13>: push ebx

0x000011ec <+14>: push ecx

0x000011ed <+15>: call 0x10b0 <__x86.get_pc_thunk.bx>

0x000011f2 <+20>: add ebx,0x2e0e

0x000011f8 <+26>: mov eax,ecx

0x000011fa <+28>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax+0x4]

0x000011fd <+31>: add eax,0x4

0x00001200 <+34>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [eax]

0x00001202 <+36>: sub esp,0xc

0x00001205 <+39>: push eax

0x00001206 <+40>: call 0x11a9 <bowfunc>

0x0000120b <+45>: add esp,0x10

0x0000120e <+48>: sub esp,0xc

0x00001211 <+51>: lea eax,[ebx-0x1ff8]

0x00001217 <+57>: push eax

0x00001218 <+58>: call 0x1040 <puts@plt>

0x0000121d <+63>: add esp,0x10

0x00001220 <+66>: mov eax,0x1

0x00001225 <+71>: lea esp,[ebp-0x8]

0x00001228 <+74>: pop ecx

0x00001229 <+75>: pop ebx

0x0000122a <+76>: pop ebp

0x0000122b <+77>: lea esp,[ecx-0x4]

0x0000122e <+80>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gdb-peda$

The difference between the AT&T and Intel syntax is not only in the presentation of the instructions with their symbols but also in the order and direction in which the instructions are executed and read.

Let us take the following instruction as an example:

0x000011e9 <+11>: mov ebp,esp

With the Intel syntax, we have the following order for the instruction from the example: Intel Syntax

| Instruction | Destination | Source |

|---|---|---|

| mov | ebp | esp |

AT&T Syntax

| Instruction | Source | Destination |

|---|---|---|

| mov | %esp | %ebp |